Land Loss Has Plagued Black America Since Emancipation – Is it Time to Look Again at ‘Black Commons’ and Collective Ownership?

This is a repost fromThe Conversation.

Authors: Kofi Boone, professor of landscape architecture, College of Design, North Carolina State University; Julian Agyeman, professor of urban and environmental policy and planning, Tufts University

Underlying the recent unrest sweeping U.S. cities over police brutality is afundamental inequityin wealth, land and power that has circumscribed black lives since the end of slavery in the U.S.

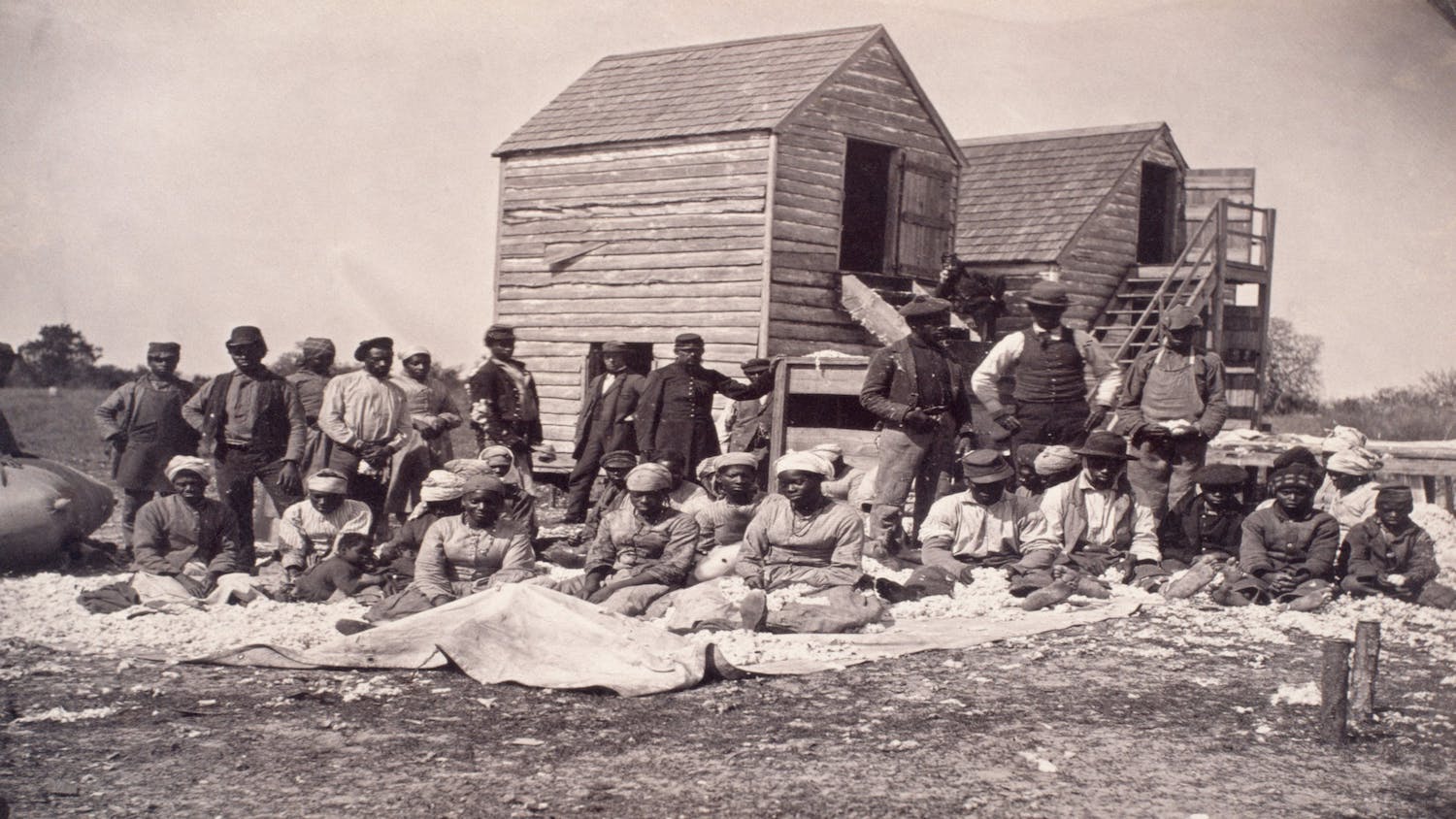

The “40 acres and a mule” promised to formerly enslaved Africans never came to pass. There was no redistribution of land, no reparations for the wealth extracted from stolen land by stolen labor.

June 19 is celebrated by black Americans asJuneteenth, marking the date in 1865 that former slaves were informed of their freedom, albeit two years after theEmancipation Proclamation. Coming this year at a time of protest over the continued police killing of black people, it provides an opportunity to look back at how black Americans were deprived of land ownership and the economic power that it brings. An expanded concept of the “black commons” – based on shared economic, cultural and digital resources as well as land – could act as one means of redress. As professors inurban planningandlandscape architecture, our research suggests that such a concept could be a part of undoing the racist legacy of chattel slavery by encouraging economic development and creating communal wealth.

Land grab

The proportion of the United States under black ownership has actually shrunk overthe last 100 years or so.

At their peak in 1910,African American farmersmade up around 14% of all U.S. farmers, owning16 to 19 million acres of land. By 2012, black Americans represented just 1.6% of the farming community, owning 3.6 million acres of land. Another study shows a98% declinein black farmers between 1920, and 1997. This contrasts sharply with anincrease in acres owned by white farmersover the same period.

Ina 1998 report, the U.S. Department of Agriculture ascribed this decline to a long and “well-documented” history of discrimination against black farmers, ranging from New Deal and USDAdiscriminatory practicesdating from the 1930s to 1950s-era exclusion from legal, title and loan resources.

Discriminatory practices have also affected who owns property as well as land. In 2017, the racial homeownership gap wasat its highest level for 50 years, with 79.1% of white Americans owning a home compared to 41.8% of black Americans. This gap is even larger than it was whenracist housing practices such as redlining否认黑人居民抵押贷款购买,or loans to renovate, property were legal.

The lack of ownership is crucial to understanding the crippling economic disparity that hashollowed out the black middle classand continues to plague black America – making it harder to accrue wealth and pass it on to future generations.

A 2017reportfound that the median net worth for non-immigrant black American households in the greater Boston region was just US$8, but for whites it was $247,500. This was due to “general housing and lending discrimination through restrictive covenants, redlining and other lending practices.”

Nationally, between 1983 and 2013, medianblack household wealth decreasedby 75% to $1,700 while median white household wealth increased 14% to $116,800.

Freedom farms

土地所有权今天可能看起来很不同。The idea of collective ownership has a long history in the United States. Even during slavery, a piece of ground was granted by slave masters for enslaved African subsistence farming. TheJamaican social theorist Sylvia Wyntercalled this land “the plot.”

Wynter has explainedhow that these parcels of land were transformed into communal areas where slaves could establish their own social order, sustain traditional African folklore and foodways – growing yams, cassava and sweet potatoes. Plots were often called “yam grounds,” so important was this staple food.

The connection between food, land, power and cultural survival was subversive in its nature. By appropriating physical space to support collective growing practices within the brutal constraints of slavery, black people also demonstrated the need for common, shared mental space to enable their survival and resistance. Herbalism, medicine and midwifery, and other African Americanhealing practiceswere seen as acts of resistance that were “intimately tied to religion and community,” according to historian Sharla M. Fett.

With the end of slavery, these plots disappeared.

The principles of collective land ownership evolved in post-slavery black America. It was central to civil rights organizer Fannie Lou Hamer’sFreedom Farms, acooperative modeldesigned to deliver economic justice to the poorest black farmers in the American South.

In Hamer’s view, the fight for justice in the face of oppression required a measure of independence that could be achieved through owning land and providing resources for the community.

This idea of a black commons as a means of economic empowerment formed a focus of W.E.B. DuBois’ 1907 “Economic Co-operation Among Negro Americans.” DuBois believed that the extreme segregation of the Jim Crow era made it necessary toground economic empowermentin the cultural bonds between black people and that this could be achieved through cooperative ownership.

Credit unions and co-ops

The accumulation of wealth was not the only desired consequence of a black commons.

In 1967,social critic Harold Cruseargued for a “new institutionalism” that would create a “new dynamic synthesis of politics, economics, and culture.” In his view, economic ventures needed to be grounded in the greater aspirations of black communities – politically, culturally and economically. This could be achieved through a black commons.

As the political economistJessica Gordon Nembhardhas notedin reference to blackcredit unions and mutual aid funds, “African Americans, as well as other people of color and low-income people, have benefited greatly from cooperative ownership and democratic economic participation throughout the nation’s history.”

The nonprofitSchumacher Center for a New Economicsis working to rejuvenate the idea of black commons. In a 2018 statement, the中心建议采用社区土地信托圣ructure“to serve as a national vehicle to amass purchased and gifted lands in a black commons with the specific purpose of facilitating low-cost access for black Americans hitherto without such access.”

Meanwhile, shared equity housing schemes andcommunity land trustscontinue to grow, helping black families own property,advance racial and economic justiceand mitigate displacement resulting from gentrification.

Digital commons

The disproportionate effects of thecoronavirus pandemicand unrest overpolice brutalityhave highlighted deeply embedded structural racism. Organizations such as Black Lives Matter and theMovement for Black Livesare demonstrating a renewed vigor around collective action and a blueprint for how this can be achieved in a digital age. At the same time, black Americans are also forging a cultural commons through events such as DJ D-Nice’sClub Quarantine– ahugely popularonline dance party. Club Quarantine’s success indicates the potential for using online platforms to facilitate community building, pointing toward future economic cooperation.

That’s what organizations likeUrban Patchare trying to do. The nonprofit group uses crowdsourced funding to build community spaces in inner city areas of Indianapolis and encourage collective economic development that echoes the black commons of years past.

The long history of racism in the United States has held back black Americans for generations. But the current soul searching over this legacy is also an unrivaled opportunity to look again at the idea of collective black action and ownership, using it to create a community and economy that goes beyond just ownership of land for wealth’s sake.

- Categories:

This is a completlyone sided view. Conclusions are made based on selective truths and warped interpretations. It echos the 1619 project which is also based on a false premise. I hate that NC State Unversity is presenting this as a factual representation of US history. This country’s history cannot be jammed thru a single lense represented in this article. This article simply markets socialist principles disguised as a moral obligation.